Concerning the Ethics of Mandatory Vaccination and the Christian Duty to Vaccinate

Vaccine mandates have been a contentious issue within the United States especially after COVID-19. Some argue that mandates infringe on civil liberties, personal autonomy, and are coercive while others argue it is necessary to keep people healthy [1]. In the United States, vaccine mandates are employed within the context of school enrollment and always have medical exemptions along with a majority of states having religious, philosophical, and personal exemptions [2]. Within the United States, some Christian groups have traditionally been skeptical of vaccination such as Dutch Reformed or the Amish; however, “judging by some recent high-profile outbreaks and various social media, even some mainstream Christian groups such as evangelical Christians and some Catholics have questioned the safety, necessity, and morality of vaccination” [3]. In response to these concerns and viewpoints, in the United States, new and stricter vaccine mandates should not be implemented other than what we already have; however, we as Christians still have a duty to vaccinate in order to fulfill the command to love our neighbor.

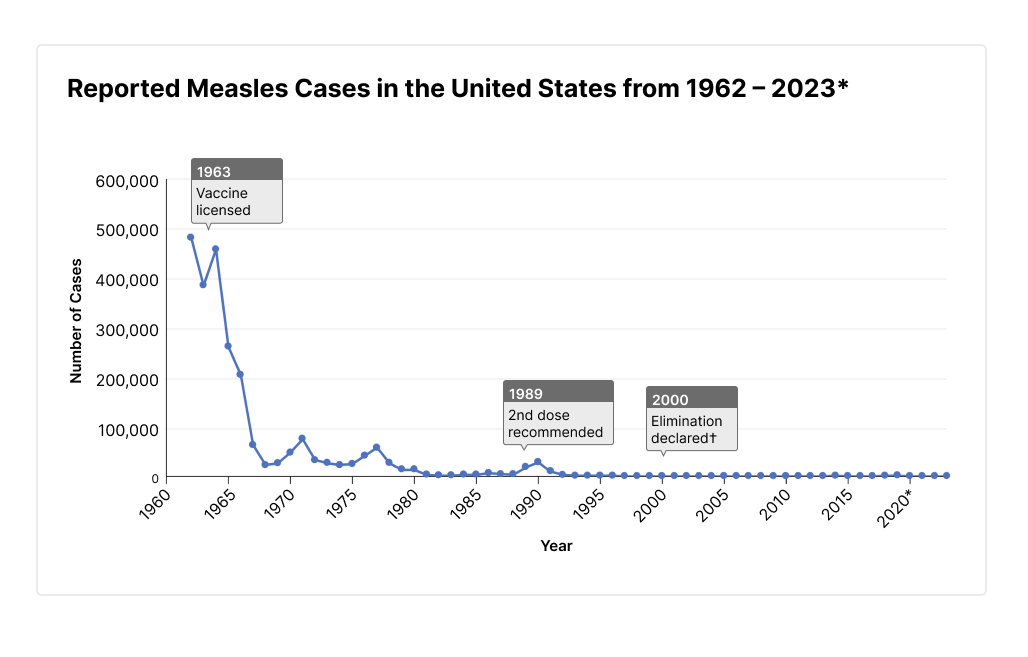

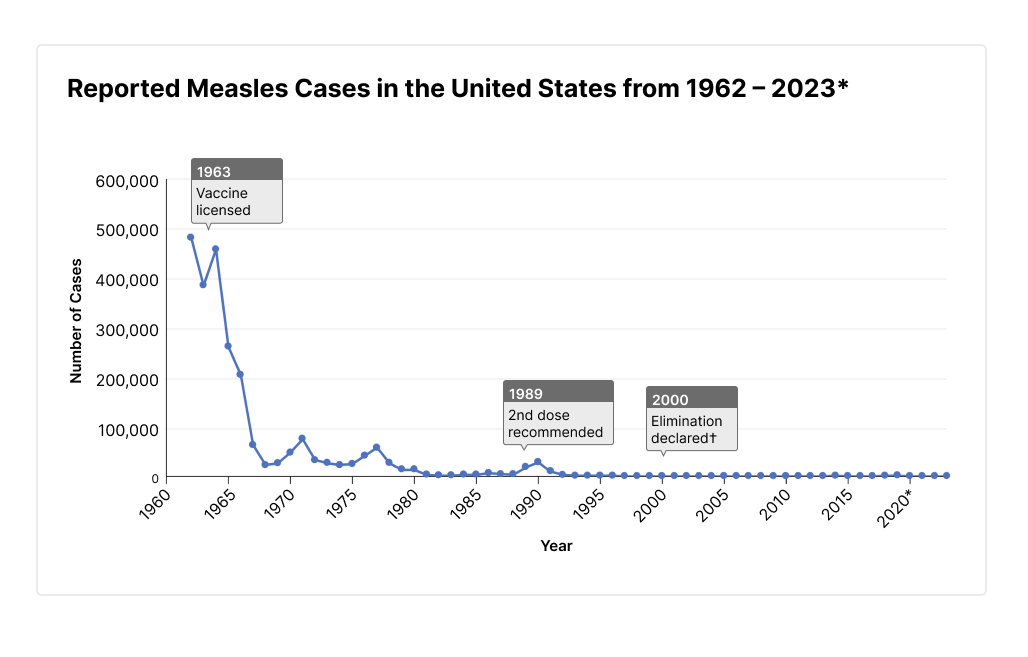

As stated prior, in the United States we have vaccine mandates in regards to school enrollment but with exemptions. I would like to consider this a ‘soft’ mandate as compared to a ‘hard’ mandate which would mean that one must get a vaccine no matter what – except for medical reasons. ‘Soft’ mandates are the way vaccine mandates should be implemented in the United States. Whenever a nation-state considers whether or not to mandate a vaccine it must look at four factors: (1) proportionality, that is, how the risk of the disease might justify restriction of freedom; (2) precedent, prior responses and laws should hold weight over the decision of the state; (3) context, the social and cultural context of the nation; and (4) sufficiency of access, meaning that the state must make the vaccine freely available to all [4]. For examining these criteria we will consider the MMR vaccine as the focus of this graphic essay so far has been on measles. I will assume that the availability of the MMR vaccine is good in the United States, so therefore we must consider the other three criteria.

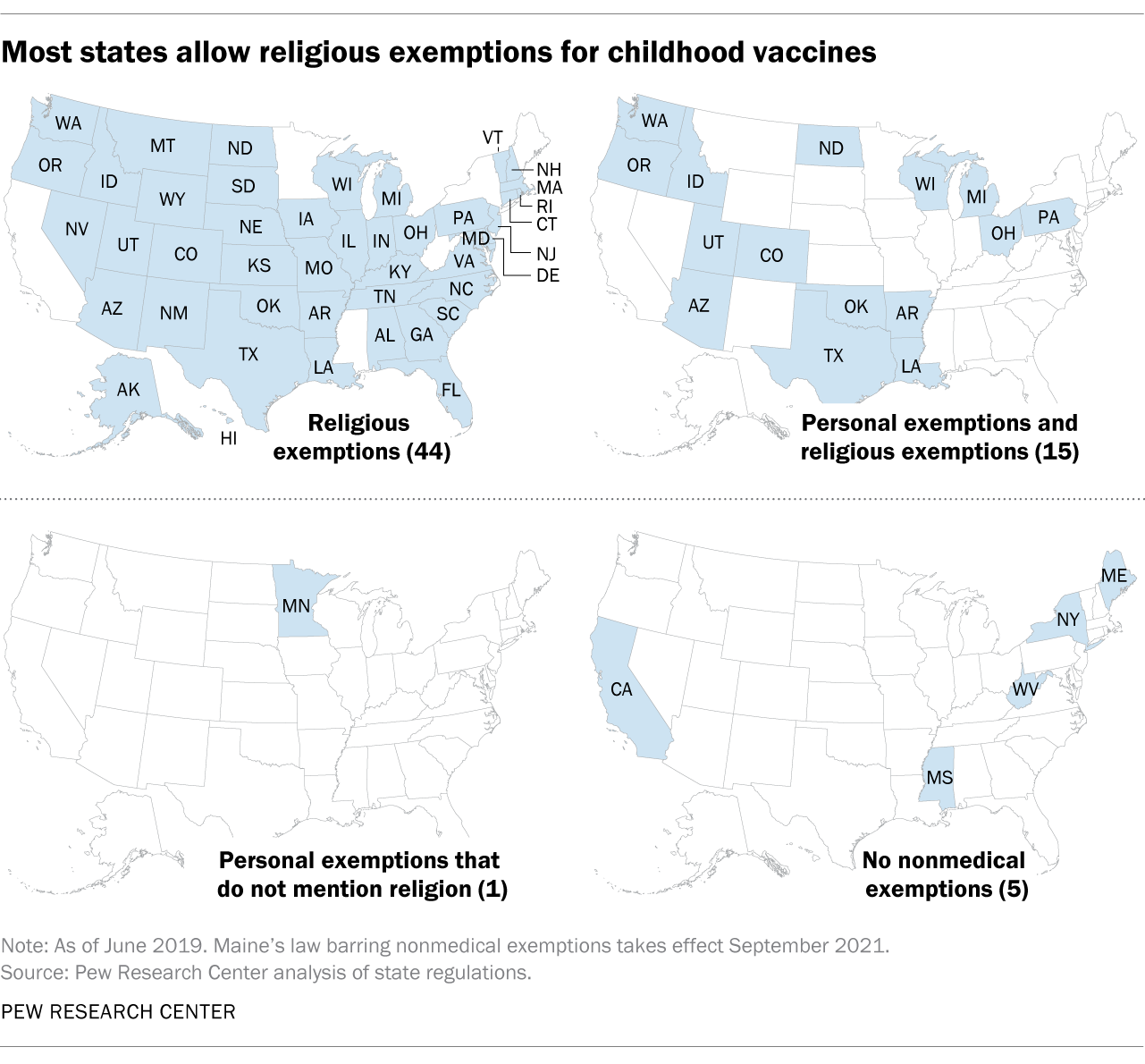

First of all, I would like to consider context and precedence. The United States is a nation that is founded on the principles of personal liberty and autonomy. Therefore, it is more difficult to justify actions by the state that would limit an individual’s autonomy, especially when it concerns that person’s health. The state needs to consider this context as the cultural expectation of its constituents is that the state will not infringe on their personal liberties. Furthermore, while vaccine mandates exist in the US to some extent, they are limited to some extent on the side of the state meaning there are exemptions. In every state, there are medical exemptions to vaccine mandates which is, of course, a reasonable exemption to be had. Also, there are religious, personal, and philosophical exemptions to vaccines. Whether or not one considers these exemptions to be reasonable is somewhat irrelevant as we have to consider the precedence that this sets which is one of ‘soft’ mandates. In order to justify a ‘hard’ mandate in the United States then we have to consider proportionality.

Regarding measles, it is quite a deadly disease, and it is estimated to have caused more than “4 million deaths per year worldwide in the prevaccination era” [5]. Comparatively, the MMR vaccine is quite safe, for example, encephalitis occurs in around one in a million doses compared to one in a thousand cases of measles [6]. Furthermore, the measles vaccine provides 97% protection after two doses and requires a population-wide vaccine coverage of 95% to achieve herd immunity [7]. As should be clear, the risk of vaccination is significantly lower than contracting the disease, and measles is not a good disease to get. However, in the United States, does this mean the state should implement a ‘hard’ mandate for the MMR vaccine? I argue no, and this is due to the precedence and context within the United States. Furthermore, one could argue that the infringement of personal liberties is a greater harm than that of contracting the disease. Michael Kowalik argues that we have to consider if an individual contribution to herd immunity offsets the harm associated with “coercively depriving a person of bodily autonomy with respect to a potentially life changing or otherwise irreversible decision about self-constitution.” He claims that bodily autonomy is as valuable as life, and therefore, we should regard every permanent violation of bodily autonomy as a partial destruction of agency and, by extension, life [8]. Furthermore, vaccination is not ethically comparable to mandatory seatbelts or forcibly taking something dangerous from a child as it permanently alters a person’s constitution. It is irreversible and not just a behavioral preference [9].

However, is it possible to achieve herd immunity then? And what about ‘soft’ mandates? Well, first, I would argue that ‘soft’ mandates heavily encourage people to vaccinate, but do not absolutely require them to do so. It allows room for genuine medical, religious, or personal reasons to not get vaccinated. However, there are genuine reasons to get vaccinated, especially since they are safe. The most important thing to do is comprehensive, understandable, and respectful education on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. The state must make it easy for parents to acquire accurate and understandable information about vaccines [10]. Through this, it is possible to achieve and maintain herd immunity and dispel vaccine hesitancy.

While the state should not impose ‘hard’ vaccine mandates, what should the Christian orientation towards vaccination be? Does the Christian have a moral duty to vaccinate? I argue yes. One way to look at this is through the ideas found within Catholic Social Teaching (CST). While I am not myself Roman Catholic – I am a traditional Protestant – I think CST is a useful framework for discussing Christian ethics especially in the modern world. We must first consider the virtue of solidarity which is promoting the common good. For us, “the duties flowing from solidarity both commit [Christians] to acting for the benefit of others and are non-optional because solidarity itself is an essential moral virtue to which all [Christians] are called.” Flowing from solidarity are the values of justice and love. Justice refers to giving one that is their due – a minimal ethical demand – where love goes further by “actively seeking the good of the other as other and the common good of all” [11]. Furthermore, the virtue of solidarity and the “principles and values [flowing from it] entail a duty to vaccinate.” We indirectly harm others and “forsake solidarity” if we refuse to vaccinate. We fail to help protect others against disease and protect society at large from disease, and it is also “contrary to the civic and political love that should be shown to all.” Thus, “vaccinating ourselves expresses our love for the medically vulnerable and demonstrates our commitment to the common good by seeking and promoting the health of all” [12].

Therefore, Christians have a calling to eschew their rights – in this case the right to personal autonomy – in order to promote the good of another. However, where can we find this in Holy Scripture? Well, it can be found in the sections in 1 Corinthians where Paul talks about eating sacrificed foods and not being a stumbling block for others, for example: “‘All things are lawful,’ but not all things are helpful. ‘All things are lawful,’ but not all things build up. Let no one seek his own good, but the good of his neighbor” [13]. Paul in 1 Corinthians is talking about how the Christian is supposed to not be a stumbling block for others, whether that be fellow brothers and sisters in Christ or nonbelievers, even if a behavior is well within their rights to do. Thus, Paul is elevating the principles of love and building up others over the freedom and rights one possesses [14]. While the context of the passages surrounding this debate concern eating food sacrificed to idols, the underlying principles can certainly be applied to the question of vaccination. According to Paul, Christians have a duty to promote the good of others even if it causes sacrifice on our part, and this principle is much like the virtue of solidarity as expounded upon in my discussion on CST. Thus, Christians have a duty to vaccinate especially since the risk is so small to the individual and the benefits extremely great for society at large. However, I argue that this does not mean we ought to apply this principle to everyone in the society as not all are Christians. This Christian virtue, while laudable, is not to be enforced onto all within a secular nation as not all are Christian and it renders the virtue null, as it does not flow out of a genuine conviction to enshrine said virtue, but out of coercion.

"Let no one seek his own good, but the good of his neighbor" - St. Paul